Just when you think you know all there is to know about the principal figures of Hollywood’s golden age, along comes this knockout of a book about the little-known Joan Harrison. Educated at Oxford and the Sorbonne, she answered a want ad for a secretarial job at Gaumont British Pictures in 1933 and within a few short years was collaborating with Alfred Hitchcock on the screenplays of Young and Innocent, The Lady Vanishes, Rebecca and Foreign Correspondent. She also became an indispensable colleague who traveled and lived with the Hitchcock family. In the 1940s she set off on her own as a producer when few women held that title, and rejoined Hitchcock as the executive producer of his long-running television series.

Those are just the bullet points of an impressive life and career. One wouldn’t expect an intimate biography of a person who died in 1994 and spent her later years outside the spotlight, but Christina Lane has done the near-impossible. This eye-opening book is not only a valuable contribution to film literature but a compelling read. The author paints a vivid portrait of a woman who held her own in a male-dominated business, developed strong female characters in her stories, and cut a fashionable figure in Hollywood social circles. One could say that she was the ultimate Hitchcock blonde. Consider this book a “must.”

HOME WORK by Julie Andrews and Emma Walton Hamilton (Hachette)

I was raised with the belief that movie stars lived in an alternate reality, untouched by the problems that mere mortals have to contend with. Julie Andrews set the record straight in her first memoir, Home, a candid and revelatory look at her challenging young life. Home Work picks up where that book left off, as she comes to Hollywood with her husband and daughter to make her first film, Mary Poppins.

Her memories of that unique experience are a joy to read, as is her follow-up chapter on The Sound of Music. But her big-screen success also sowed the seeds of failure for her marriage to talented production designer Tony Walton. They no longer had a home base, as he was in demand in London and New York while each film on her agenda took her to a new location. Andrews later married writer-director Blake Edwards, a mercurial personality with two children. She details their ups and downs as a couple and as work partners whose parenting skills were put to the test on a regular basis. Written in collaboration with her daughter, Andrews’ memoir paints a bittersweet picture of a life lived to the fullest.

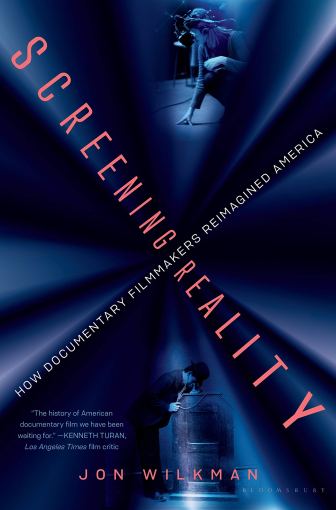

SCREENING REALITY: HOW DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKERS REIMAGINED AMERICA by Jon Wilkman (Bloomsbury)

Imagine a one-volume survey of documentary film and television that covers Robert Flaherty and Errol Morris, Michael Moore and Fred Friendly, bridging a span from actuality films of the early 20th century through the invention of Virtual Reality. You needn’t imagine it because Jon Wilkman has accomplished the near-impossible in this informative and highly readable new book. A respected documentarian himself, the author brings first-hand experience to the subject. Dip into any chapter and you’ll find yourself comparing notes (for the book is openly opinionated) or being reminded of films you want to see. It is a towering achievement, and a volume I know I’ll be consulting on a regular basis.

Railroads and trolley cars help tell the history of Los Angeles, as a city and a center of film production in the 20th century. That is the inspiration for this handsomely produced book, filled with historical information and eye-popping photos, many of which I’ve never seen before. Even the end-papers are an eyeful, offering a colorful collage of transportation-related movie posters, ranging from John Ford’s The Iron Horse to Judy Canova in Carolina Cannonball.

I never would have chosen 1962 as a watershed year for filmmaking but authors McLellan and Farber have proven me wrong. Their essays provide historical context and a well-informed look at the ingredients that meshed to make this an exceptional period for filmmakers and filmgoers alike. As I said in a blurb for the jacket cover, any year that brought forth Lolita, The Manchurian Candidate, Ride the High Country, Days of Wine and Roses and The Music Man can certainly lay claim to special significance. The fact that such adult storytelling existed side by side with standard Hollywood fare says volumes about the way mainstream American cinema has devolved over the past half-century.

REDISCOVERING ROSCOE: THE FILMS OF “FATTY” ARBUCKLE by Steve Massa (BearManor Media)

Steve Massa has become a world-class chronicler and archeologist of silent comedy, and his latest endeavor is a massive undertaking, as befits its subject. Rediscovering Roscoe is a hefty 692 pages long and incorporates 500 rare photos. It also marks the first time anyone has focused exclusively on Arbuckle’s career and its many highlights. He was an established star at Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studio before Charlie Chaplin, who became a collaborator when he arrived in 1914. He started directing his own short subjects that same year and graduated to feature-length films before Chaplin. He famously ushered Buster Keaton into the world of filmmaking. He was a talented man who was known and loved the world over. Yet the scandal that ended his career has eclipsed everything else he accomplished. That’s why this book is both overdue and welcome.